n the United States, copyright protection is afforded to original works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression. But what does it mean for something to be “fixed”? Must it be motionless? In the case of sculpture, can it be “fixed” if it can take on different poses? Here, Tangle, Inc. v. Aritzia Inc., 125 F.4th 991 (9th Cir. 2025) sheds some light–the Ninth Circuit recently held that copyright protection extends even to objects that are kinetic and manipulable in nature.

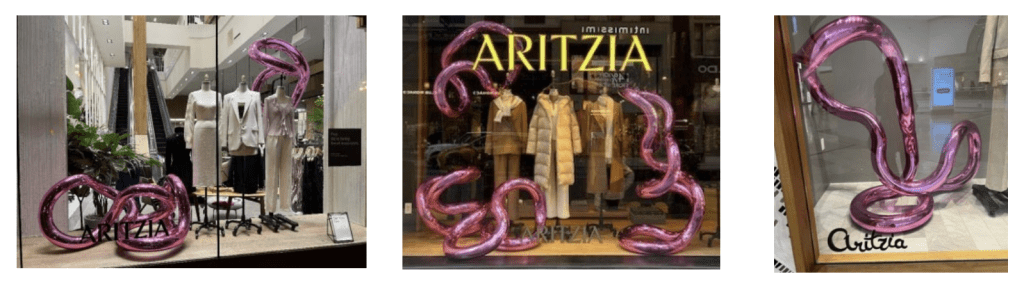

Tangle, Inc., a toy manufacturer and distributor, holds copyright registrations for its kinetic, manipulable sculptures made of numerous identical, 90-degree curved, interlocked tubular segments able to twist and turn 360 degrees where any two segments meet. By twisting the segments, the sculptures can adopt different poses (see image 1). Aritzia, Inc., in turn a retail apparel brand with stores across the U.S. and Canada, displayed a series of similar interlocked, twistable sculptures in their storefronts, albeit larger and bright pink with a chrome finish. (see image 2).

Cue litigation, Tangle filed suit against Aritzia for copyright infringement and arguing that Aritzia’s displays infringed on the “core expression” embodied in Tangle’s sculptures. At the district level, the court dismissed Tangle’s copyright claim, holding that the toy manufacturer lacked valid copyrights in its works because, by claiming ownership of every conceivable iteration of its sculptures, Tangle sought to copyright something unprotectable, namely, a particular style or amorphous idea. Emphasizing that only fixed works may be copyrighted, the court stressed that Tangle would need to allege infringement of specific works for a viable claim. Moreover, per the district court, Tangle also failed to allege that Aritzia copied protected aspect of its works. Using the extrinsic test, which assesses the objective similarities between two works to determine whether substantial similarity exists between the works’ protectable elements, the court entitled Tangle’s sculptures to only “thin” protection. This meant that Aritzia’s displays needed to be “virtually identical” for Tangle’s copyright infringement claim to proceed. However, considering various differences between the two companies’ sculptures, Aritzia’s were found not to be unlawful appropriations.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed, holding that Tangle had adequately alleged (1) valid copyrights, and (2) copying of its protected works. Notwithstanding Aritzia’s argument that Tangle’s kinetic, manipulable sculptures are not “fixed” as required by the Copyright Act, the Ninth Circuit concluded that the fact that Tangle’s works can take different configurations does not per se mean they are not “fixed.” In support, the court likened the sculptures to dance, motion pictures, and symphonies, all forms of copyrightable expression involving motion. The court also examined the Copyright Act’s definitions of “fixation,” namely that a work is “fixed in a tangible medium of expression when its embodiment in a copy is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.” 17 U.S.C §101. A “copy” is simply a material object in which a work is fixed. Id. Accordingly, Tangle’s sculptures are by definition “copies” because they are material objects. And, as material objects, Tangle’s sculptures can be perceived and reproduced for more than a transitory period. Therefore, Tangle’s expressions are fixed in a tangible medium as defined by the Copyright Act, and the sculptures garner copyright protection across their full range of motion.

The court also held that Aritzia had copied the protected aspects of Tangle’s works. Using the extrinsic test, the Ninth Circuit determined that a reasonable jury could find Tangle’s and Aritzia’s sculptures substantially similar. While individual elements (i.e. the number of segments, their uniformity, shapes, proportions, end-to-end connection, and joints allowing their 360-degree rotation) may have been unprotectable, Tangle’s selection and arrangement of these elements were. In fact, Tangle’s particular arrangements should, the court reasoned, enjoy broad copyright protection because of the many possible resulting expressions. With this in mind, the court found substantial similarity between the companies’ works, reinstating Tangle’s copyright claim.

Overall, this case marks a significant moment in copyright law, particularly for artists and designers working with kinetic, manipulable, and interactive pieces. The Ninth Circuit ruling affirms that copyright protection extends beyond static works, encompassing forms that involve movement and transformation. It is important to note, however, that this is a decision at the pleading stages, and the court has cautioned that the copyright analysis of kinetic and manipulable sculptures may be better informed with discovery and expert opinions.

Filed in: Copyright Counsel

February 13, 2025